By: Jonathan Glasser, an Associate Professor in the Department of Anthropology at William & Mary, and Resident Fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Paris in 2019-2020. He is the author of The Lost Paradise: Andalusi Music in Urban North Africa (University of Chicago Press 2016), which received the L. Carl Brown AIMS Book Prize from the American Institute for Maghrib Studies and the Mahmoud Guettat International Prize in Musicology (2nd place) from the Tunisian Ministry of Cultural Affairs. His work has appeared in International Journal of Middle East Studies, American Ethnologist,Anthropological Quarterly, and Anthropology and Humanism. He is currently writing a book on Muslim-Jewish musical relationships in Algeria.

What are we to make of this photograph?

Or this one? At first glance, they look like late-nineteenth century images from a North African café, featuring a group of musicians, dancers, and servers.

But if we widen our perspective …

… they turn out to be images from France—from the Algeria pavilion at the 1889 World Exposition in Paris, to be exact.

In many ways, these photographs, conserved at the National Library of France, are a familiar kind of image for students of colonial North Africa, who are attuned to the role of metropolitan representations of otherness in European imperial projects. However, I approach these images and their companion portraits somewhat differently. These are colonial representations, but they also document a milieu that, while embedded in the colonial, is not reducible to the colonial. How can we use the colonial without falling for its totalizing power? As a student of urban Maghribi performance culture, and at the present time more particularly of Muslim-Jewish relationships around music in Algeria, these photographs and the event it memorializes provide an opportunity to think through this question.

The biggest blank on the historical map of urban Algerian musical life in the modern period is the era before the French conquest of Algiers in 1830, an event that is often depicted as a cataclysmic break. Another blank is the moment just before the rise of the turn-of-the-century movement to revive the Arabic-language art music tradition known as Andalusi music. The comparative obscurity of the second half of the nineteenth century stems from a lack of recordings and from the generally humble status of professional musicians. It might also stem from the success of the revival movement itself, which tended to stress the poverty of the nineteenth-century musical scene, the decay of repertoire due to hoarding and the vagaries of oral transmission, the power of the phonograph, and revivalists’ own heroic status as rescuers and reformers of an endangered musical patrimony. Yet looking more closely at the early twentieth-century revival scene, including with respect to the Muslim-Jewish question, opens up some possible routes toward the blank spaces on the nineteenth-century map. In turn, filling in these blanks might allow us to view revival and its aftermath in new light.

Sfindja, the instrumentalist to the left, with Algerois Muslim music enthusiasts. The other instrumentalist, Mohamed ben Teffahi (1870-1944), would be a leader in the association movement in the 1930s.

For students of Muslim-Jewish relationship in Algeria and the wider Maghrib, the musical milieu of the revival era offers much to think about. Andalusi musical revival in Algeria involved both Muslims and Jews, as well as some French Christians. Despite patterns of confessionalization in some contexts, and notwithstanding the separations effected by the granting of Algerian Jews French citizenship through the Crémieux Decree of 1870, relations of discipleship often crossed religious lines. This is particularly visible in the first two decades of revival, when the shoemaker-turned-musician Mohamed Ben ‘Ali Sfindja (d. 1908), who traced his musical lineage back to the favorite singer of the last Ottoman Dey of Algiers, was held up as the final inheritor of the Andalusi repertoire in Algiers. Algerois Muslim music enthusiasts cultivated relationships of patronage and discipleship with Sfindja, and the singer was featured by the French journalist Jules Rouanet (1858-1944) in his lecture-demonstration on Algerian music at the 1905 Orientalist Congress in Algiers.

Edmond Nathan Yafil, flanked by his 1904 collection in Arabic and Judeo-Arabic. Photo of Yafil from the collection of Mme. Yamina Yahi

Arguably the most influential figure in the revival, an Algerois Jew named Edmond Nathan Yafil (1874-1928), likewise presented himself as Sfindja’s disciple. Yafil in turn was the teacher of the young Muslim singer and actor Mahieddine Bachetarzi (1897-1986), who would go on to be a founding figure in Algerian popular theater. The still vigorous network of amateur musical associations that Yafil helped found would be comprised of Jewish and Muslim members up until Jews’ mass departure at Algerian independence in 1962, and Sfindja’s name continues to resound in local narratives of revival today.

But as is common in such genealogies, many people are left out, such as the professional musicians, both Jewish and Muslim, male and female, who wove their way in and out of the association scene as teachers but who often came from more humble backgrounds than their middle-class students. There were other elder masters of the Andalusi repertoire who were close in age to Sfindja but about whom virtually nothing is known, such as the enigmatic Jewish master called Ben Farachou, who outlived Sfindja by some years but unlike him seems never to have been recorded. And reaching back into the nineteenth century, we know very little about the life of music and musicians beyond a handful of names. Perhaps most vexing for thinking about Muslim-Jewish relationships, one of the few contemporary sources on music in Algiers in the nineteenth century, published by the Russian visitor Alexander Christianowitsch in 1863, paints a picture of rivalry between high-prestige Muslim performers (including Sfindja’s teachers) associated with performance in private homes and low-prestige Jewish performers associated with cafés.

This relative obscurity and these hints of contradiction make the photographs from the Algeria pavilion in 1889 a goldmine. This is particularly so because the photographer, the physical anthropologist Prince Roland Bonaparte, noted names, ages, and professions, which has allowed me to match some of the people depicted with their civil records. There is a lot happening in these photographs, and there are offstage East-West connections to the musicians and dancers in the Moroccan and Tunisian pavilions as well. However, I’m going to bracket some of the figures on the sides, many of whom were probably from distinct ensembles featured at the Algeria pavilion, brought in to fill out the scene, to instead focus on the musicians and dancers who are center stage.

Abderrahmane Lounes

Laho Seror

Mouzino

Sheet music published by Yafil with Seror

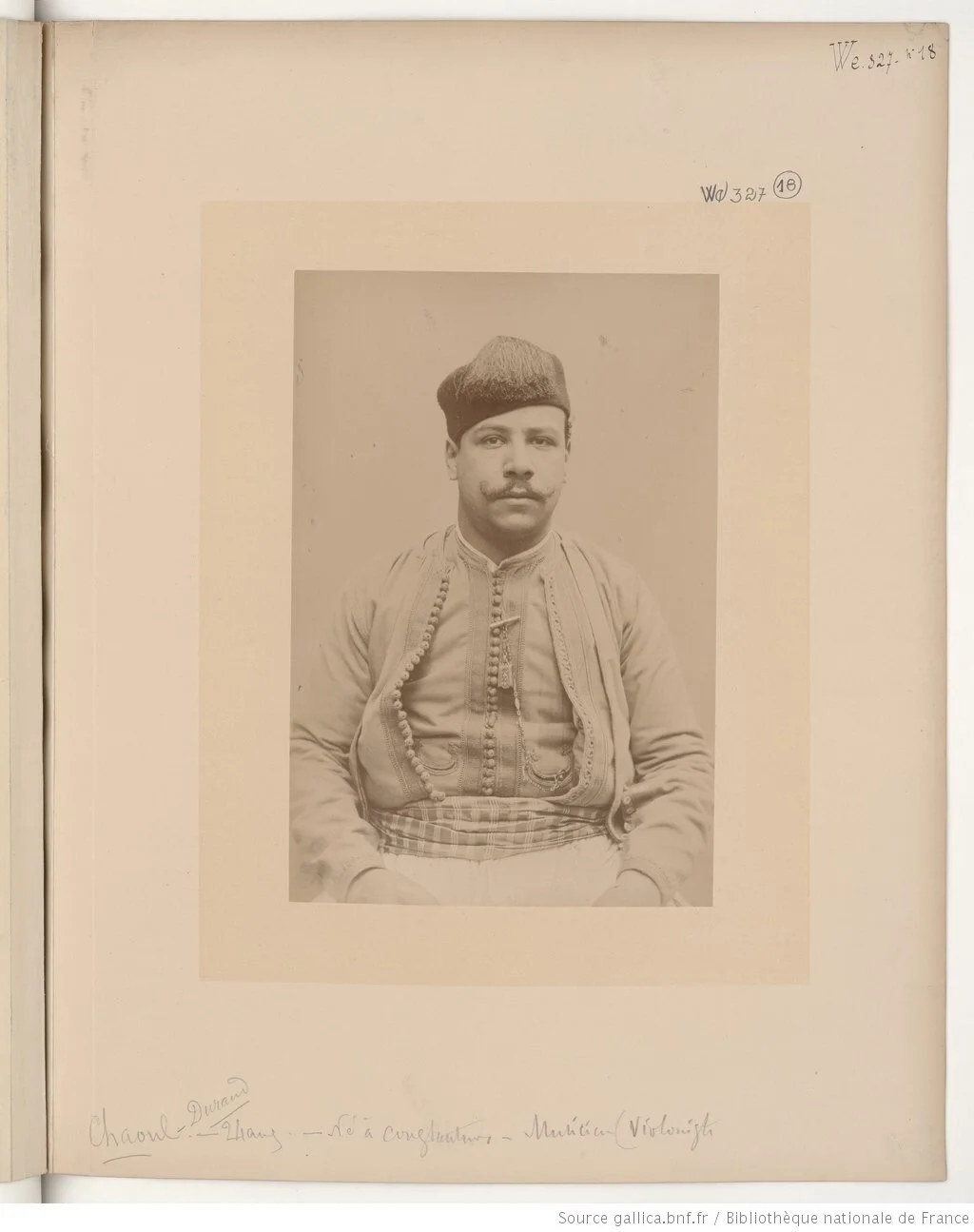

Starting with the men, there is one percussionist in the right-hand corner who I was not able to trace beyond his Muslim name, Abderrahmane Lounes (born circa 1861). The other three central male instrumentalists were all Jewish, and two of them would become central figures in the early twentieth-century revival. One of them, the shoemaker Laho Seror (1860-1940), pictured on the Algerian instrument called kuwītra, would be a close collaborator with Yafil, helping him to publish his sheet music collection and his influential compendium of song texts. Seror would also be an important teacher in the association scene all the way into the 1930s. Similarly, Chaouel Durand, on violin, better known as Mouzino (1865-1928), would collaborate with the younger Yafil, teach in the associations until his death, and be an early voice and entrepreneur in the recording industry. In addition, both Seror and Mouzino were students, accompaniers, and reputed musical inheritors of Sfindja.

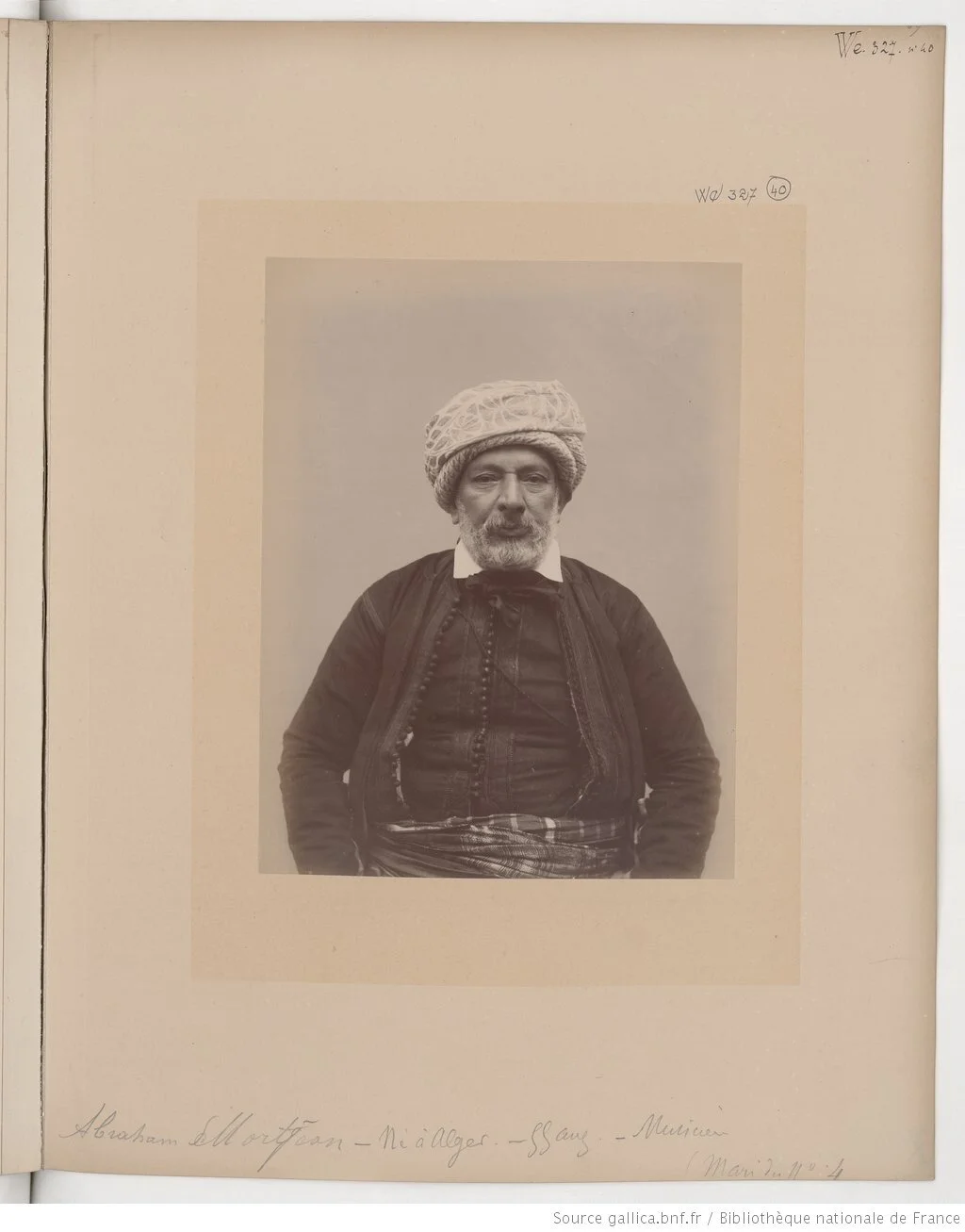

Abraham Mordjan

The more obscure figure is the shaykh at the center playing rabāb, an instrument that often sits at the heart of the traditional Andalusi ensemble. Abraham Mordjan (born circa 1828 d. 1910), who was around sixty at the time of the Exposition, was one of three half-brothers who were professional musicians in Algiers and beyond, all of them living in very modest circumstances. Interestingly, family naming patterns and his age hint at a family connection between Mordjan and the enigmatic figure of Ben Farachou, who stood in the same genealogy of musicians as Sfindja. Whether or not there was a connection to Mordjan, Ben Farachou’s lineage complicates the notion, inherited from Christianowitsch, that there was a clear division between allegedly high-prestige Muslim performers and allegedly low-prestige Jewish performers in the nineteenth century.

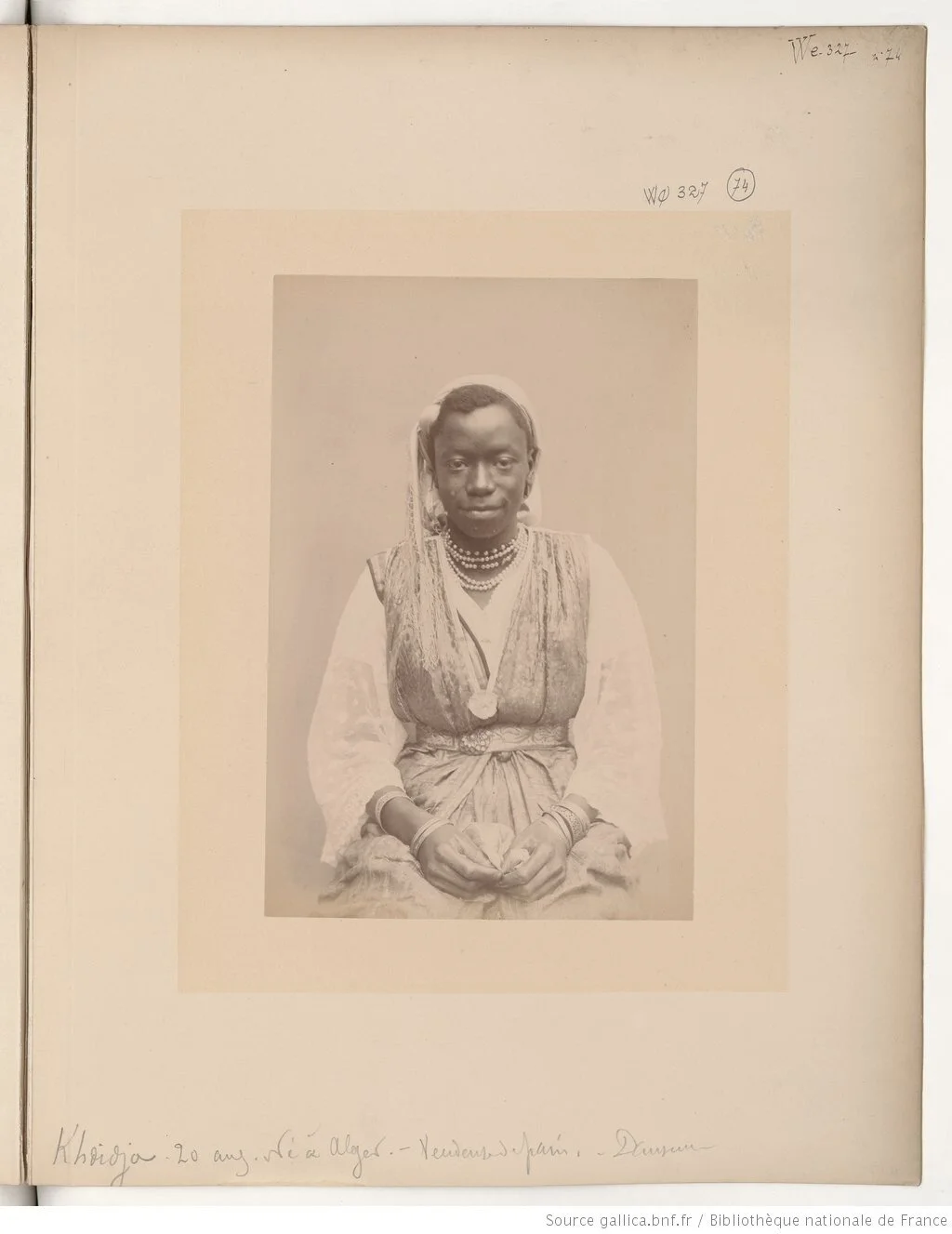

Khadidja from Algiers

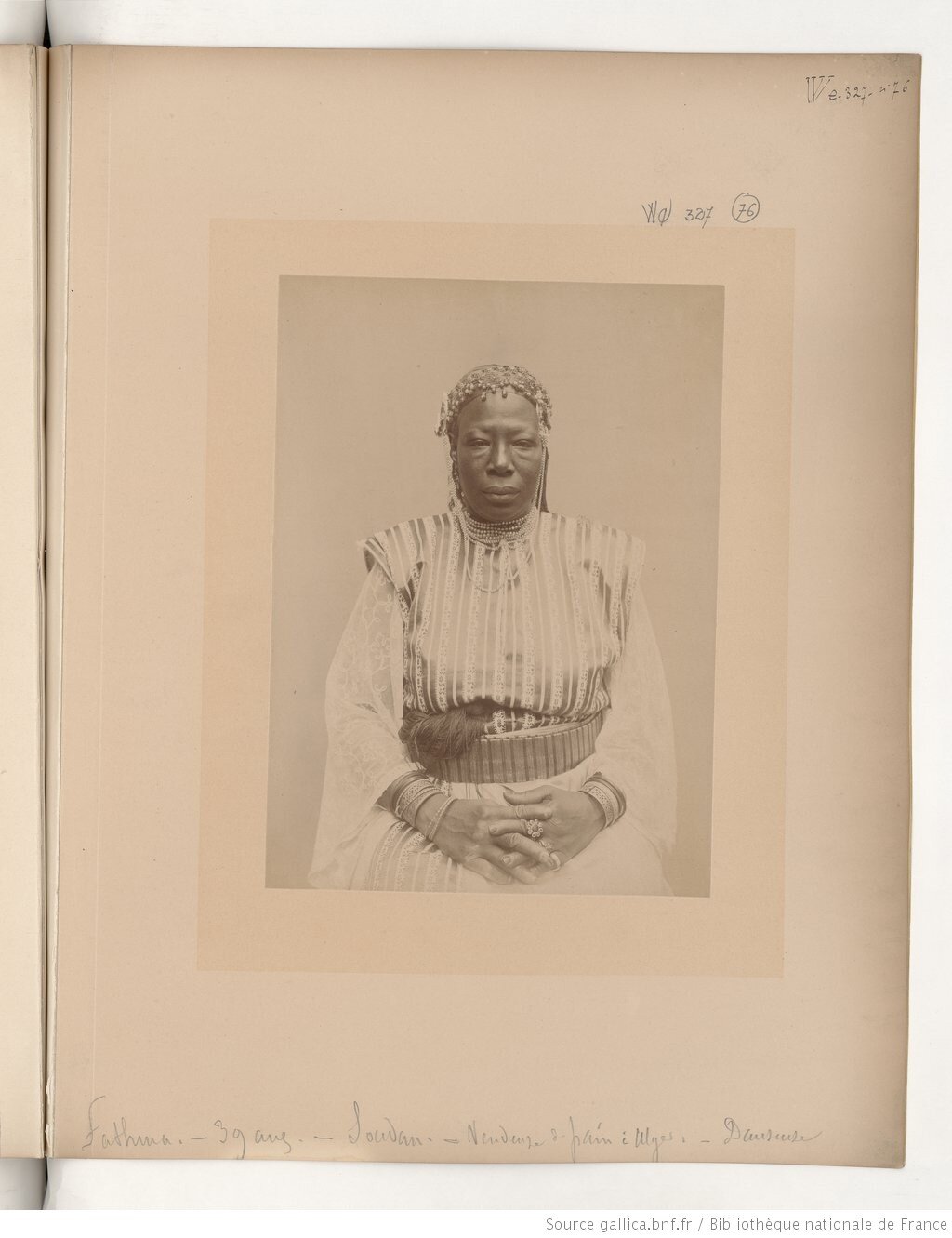

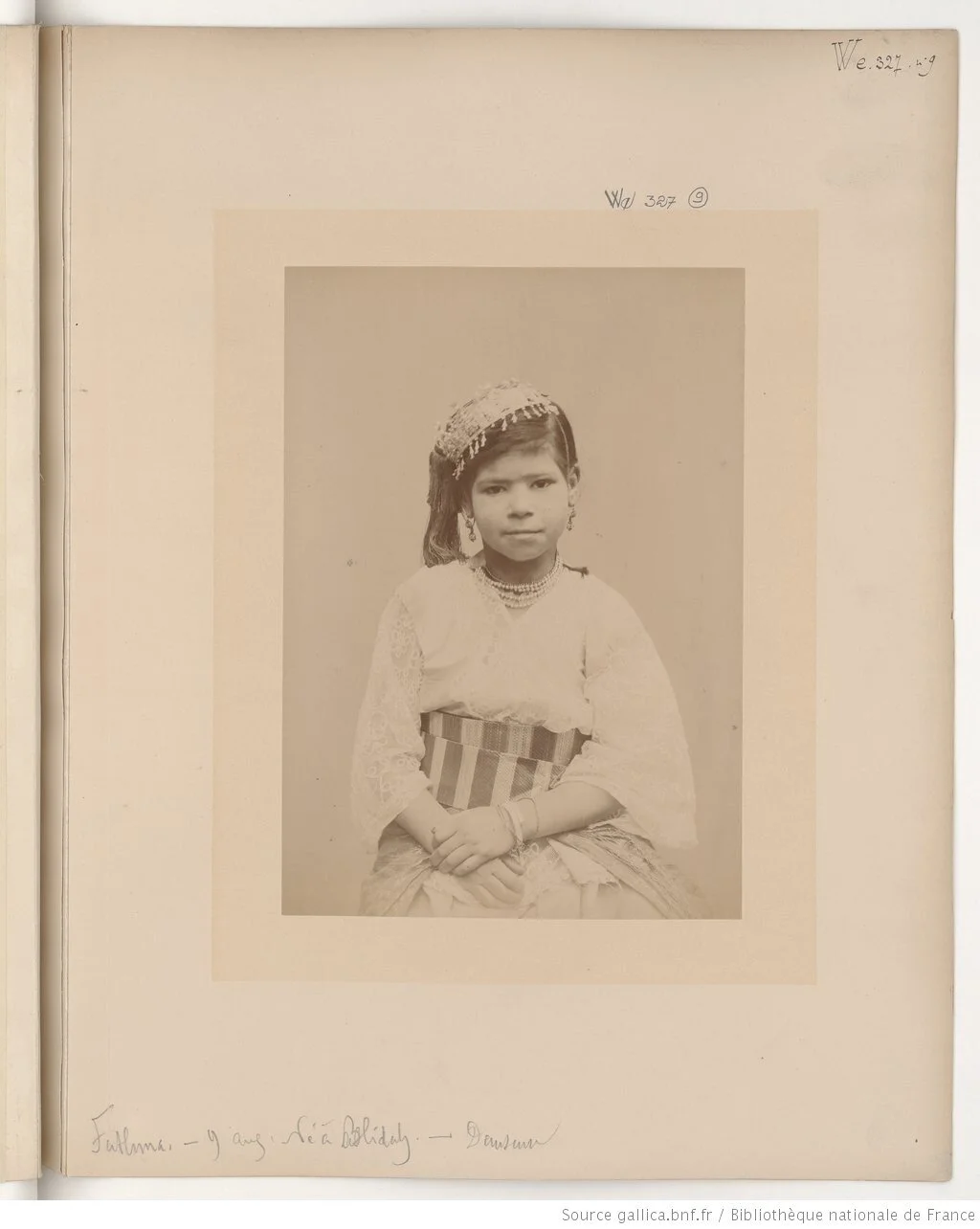

Biographically, things become considerably vaguer when we turn to the female performers. The penciled captions on the portraits state that two dancers also worked as bread sellers, the younger born in Algiers, the older in Sudan. The nine-year-old dancer is from Blida, a city known for the popular arts.

Fatima from Sudan

Fathma, the child dancer from Blida

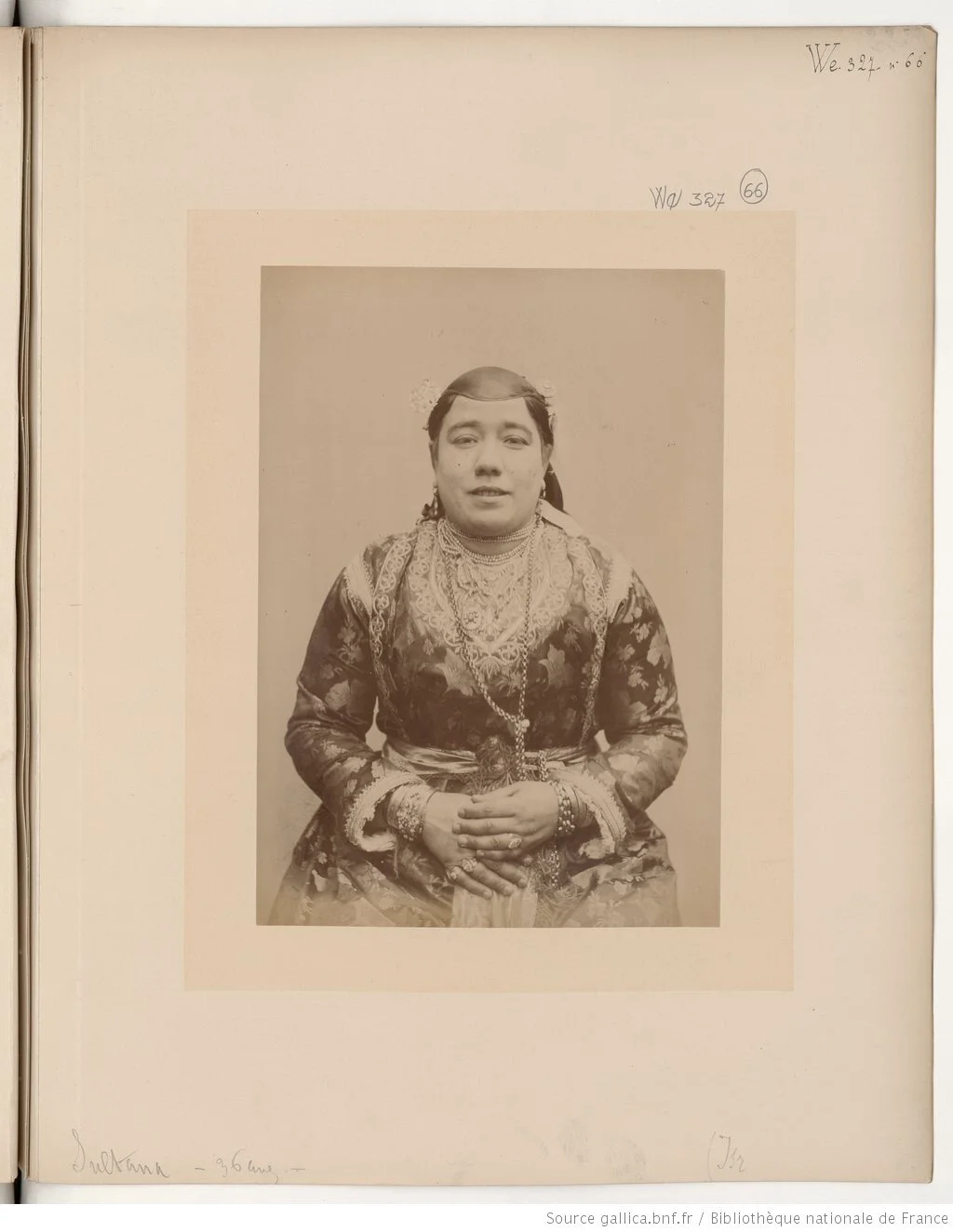

Two young seamstresses from Algiers play darbouka, one Muslim, one Jewish, the latter the daughter of a carpenter and seamstress who travelled with her and her sister to Paris. And the other two dancers, one in performance, the other perhaps awaiting her turn, were likely Muslims born to the east. Finally, there is the 36-year-old kuwītra-player sitting to Mordjan’s left, a Jewish woman named Sultana.

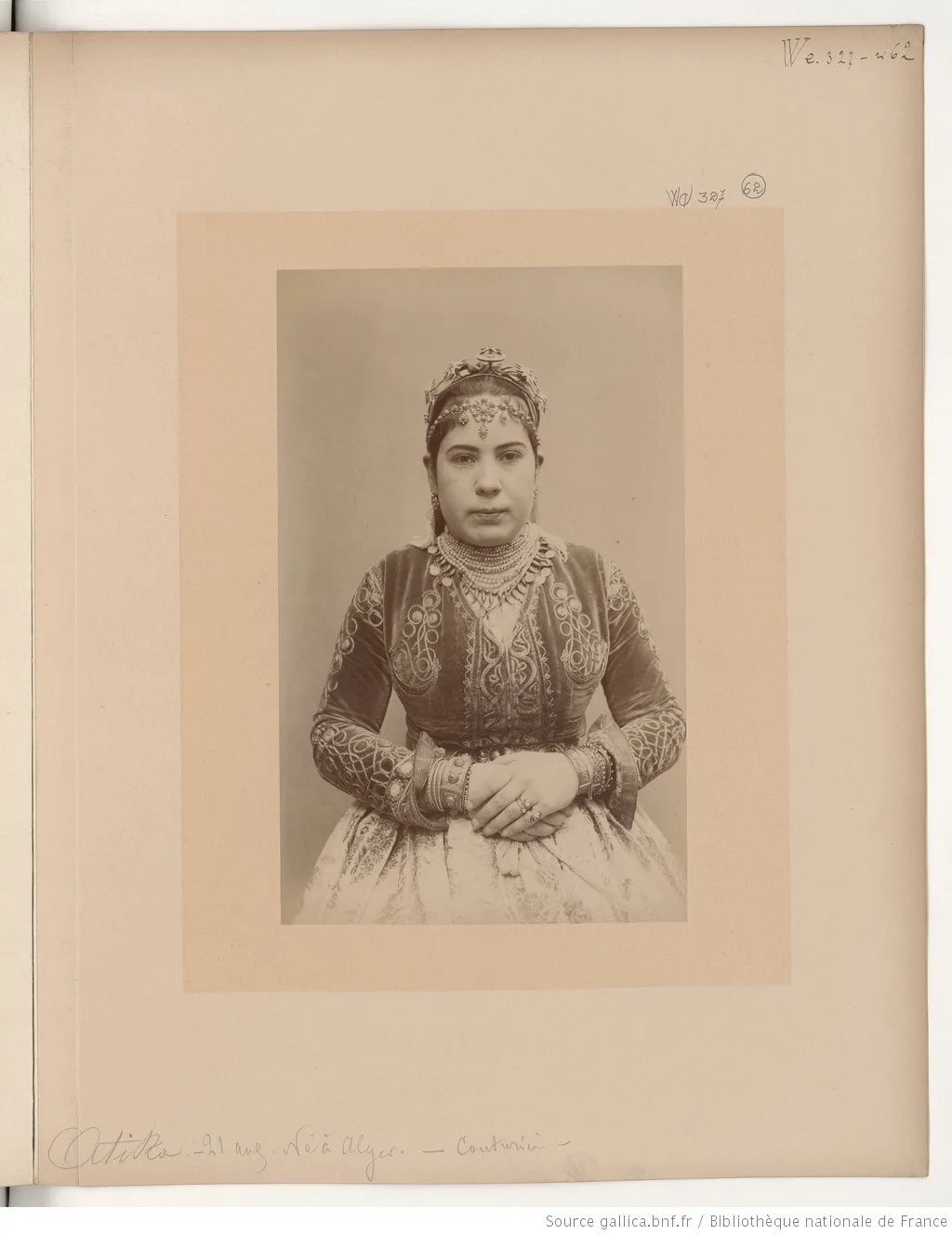

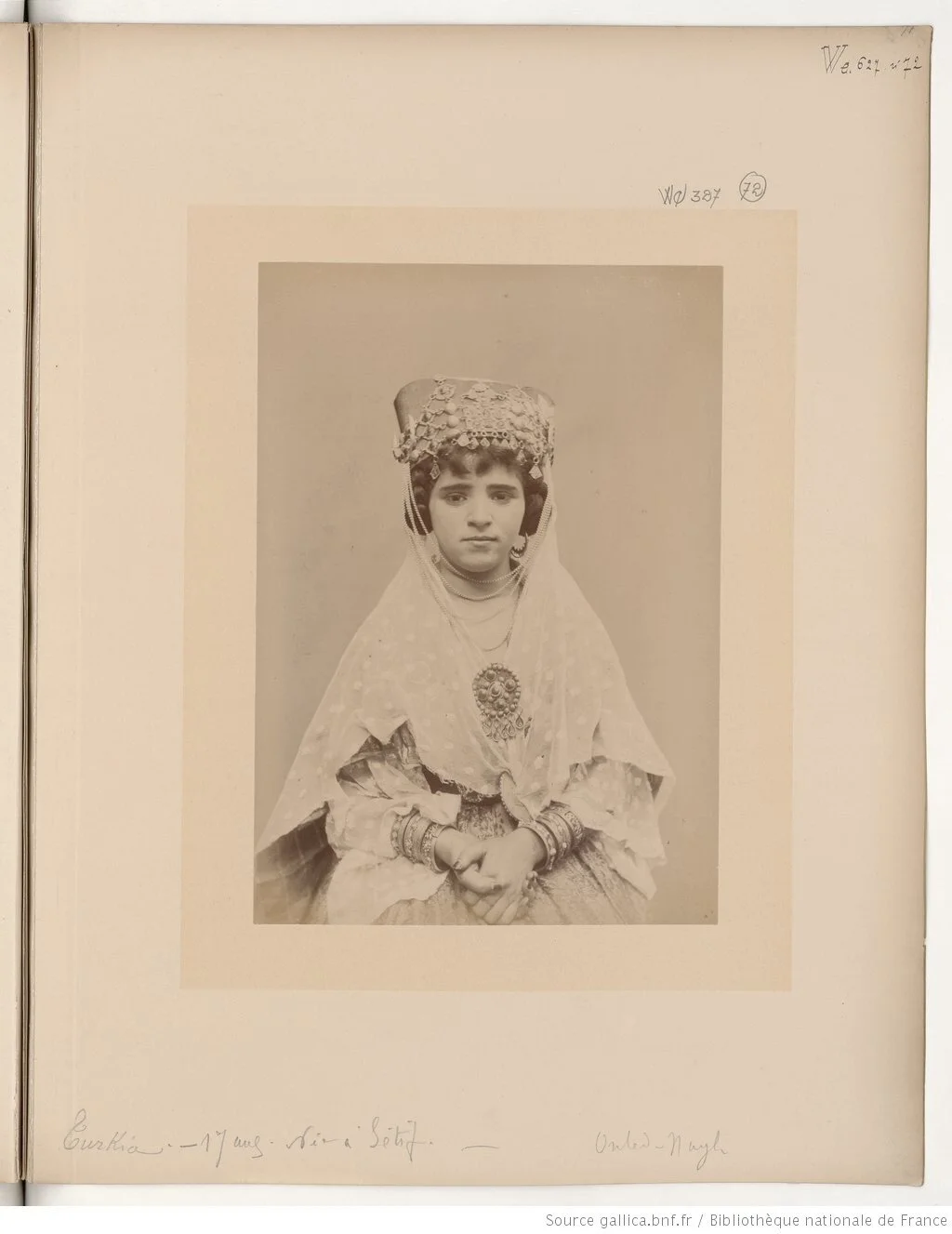

Top Left: Atika; Top Right: Yamina Chetrite; Bottom Left: Turkia from Setif; Bottom Right: Yasmina from Tizi Ouzou

Sultana

While we have few biographical details about the women in these photographs, we can form a few hypotheses. First, some of them were probably part of groups of professional female musicians and dancers in Algiers known for centuries as msemm‘āt, whose chief audience would have been female. Second, some of them were also likely prostitutes or courtesans, a longstanding social category with strong traditional links to music and dance that was also in the process of massive transformations under the colonial system. This status is particularly likely for Sultana given her age, unmarried status, clothing, and perhaps even the instrument she is playing.

If we can resist being captivated solely by their Orientalizing aspects, photographs such as these are invaluable sources for thinking about the prehistory of the Algerian musical revival, as well as for thinking about the moment of revival itself. They also have the potential to teach us a great deal about Muslim-Jewish relationships around music. It is not only a confirmation of the prominence of Jews in the ranks of professional urban musicians in the Maghrib, including in the context of the 1889 Exposition, where they were central to the dance and musical acts in all three Maghrib pavilions. It also points to the close connections between Muslim and Jewish performers, male and female, living in popular Arabic-speaking milieus, precisely at a time when Muslims and Jews were being separated by colonial law. These sorts of documents in turn allow us to start asking questions about the blank spots on the map, including the way that the Muslim-Jewish musical question fits into broader frameworks of social class, sexuality, genre, and genealogical memory. Finally, these photographs gesture toward the late Ottoman period, thereby holding out the promise that by situating the colonial within a wider context, we might overcome some of the more stubborn habits of historical periodization for the Maghrib. In this manner, we may be able to read colonial documents in such a way as to break the colonial spell.

Selected Reading List:

Bachetarzi, Mahieddine. 1968. Mémoires, 1919-1939. Algiers: SNED.

Bouzar-Kasbadji, Nadya. 1988. L’emergence artistique algérienne au XXe siècle. Algiers: Office des publications universitaires.

Christianowitsch, Alexandre. 1863. Esquisse historique de la musique arabe aux temps anciens. Cologne: Dumony-Schauberg.

Glasser, Jonathan. 2016. The Lost Paradise: Andalusi Music in Urban North Africa. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Grangaud, Isabelle and M'hamed Oualdi. 2014. ‘Tout est-il colonial dans le Maghreb? Ce que les travaux des historiens modernistes peuvent apporter.’ L'Année du Maghreb 10: 233-54.

Guedj, Jérémy. 2009a. ‘La Musique judéo-arabe: patrimoine de l’exil’. In Driss El Yazami, Yvan Gastaut, and Naïma Yahi (eds). Générations. Un siècle d’histoire culturelle des Maghrébins en France. Paris: Gallimard: 148–56.

Miliani, Hadj. 2011. ‘Crosscurrents: Trajectories of Algerian Jewish Artists and Men of Culture since the End of the Nineteenth Century’. In Emily Benichou Gottreich and Daniel J. Schroeter (eds). Jewish Culture and Society in North Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press: 177–87.

Rouanet, Jules. 1922. “La musique arabe dans le Maghreb.” In Albert Lavignac, ed. Encyclopédie de la Musique. Paris: Delagrave.

Saadallah, Fawzi. 2010. Yahud al-Jaza'ir: Majalis al-Tarab wa-l-Ghina’. Algiers: Dār Qurṭuba.

Silver, Chris Benno. 2017. ‘Jews, Music-Making, and the Twentieth-Century Maghrib’. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of California Los Angeles.

Taraud, Christelle. 2003. La Prostitution Coloniale : Algerie, Tunisie, Maroc (1830-1962). Paris: Payot.

Théoleyre, Malcolm. 2016. ‘Musique arabe, folklore de France? Musique, politique et communautés musiciennes en contact à Alger durant la période coloniale (1862-1962)’. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Sciences Po.

Yafil, Edmond Nathan. 1904. Diwān al-aghānī min kalām al-andalus. Algiers: Yafil.

-------. 1904. Majmū‘ al-aghānī wa-l-alḥān min kalām al-andalus. Algiers: Yafil.

Yafil, Edmond Nathan and Jules Rouanet, eds. 1904-. Répertoire de musique arabe et maure: collection de mélodies, ouvertures, noubet, chansons, préludes, etc. Algiers: Yafil and Seror.

Acknowledgments: This text benefitted from comments and leads from Naomi Davidson, Peter Kitlas, Ouail Laabassi, and Chris Silver.